Buen Vivir: An old, but fresh perspective on global development

A guest post by Savannah Hicks

As I sat in my cap and gown, I reflected on the broad range of global development issues I had been exposed to my Masters in Development Practice from University of California at Berkeley over the previous two years. For the first year and a half, I had been exposed to a lot, from international political economy to program management for UN programs to global leadership in business to community-based participatory methods.

But then I arrived to Thousand Currents. To conclude my studies, I worked with Thousand Currents to complete a culminating capstone project. The goal? To better understand the concept of buen vivir and how it could be assessed. No other prominent development assessment framework or approach I had learned about in my Masters program reflected the deep and complex issues inherent in buen vivir.

Buen vivir has existed as a worldview for millennia and, at its core, is about communities living sustainably with mother nature. However, it is a much deeper, complex, cultural, and spiritual concept than most of us can initially comprehend – at least those of us who grew up only within a Western, linear worldview. In it is profound depth beyond my initial understanding of community sustainability.

Defining Buen Vivir

In partnership with Thousand Currents, I conducted thorough research on what buen vivir means to some of the many communities who hold this worldview, starting with the presentation by Maria Estela Barco Huerta of DESMI (Desarrollo Económico y Social de los Mexicanos Indígenas, Asociación Civil or Civil Association for Economic and Social Development of Indigenous Mexicans) to the Thousand Currents team here in San Francisco. Maria Estela eloquently described buen vivir as being based on a concept of a deep, great respect, or Ich’el Ta Muk in the Mayan language, that each person has for the spirit, or Ch’ulel, of every other living being, which includes humans, animals, nature, and the spiritual realm. This culturally ingrained respect obligates the responsibility to care for all other beings, to identify areas for social change and to work collaboratively improve yourself and your community however you can. It allows for a plurality of perspectives, opinions, and ways of life; if you respect the spirit of everyone and everything else, you are obliged to acknowledge their inherent dignity and honor their personal life experiences and perspectives.

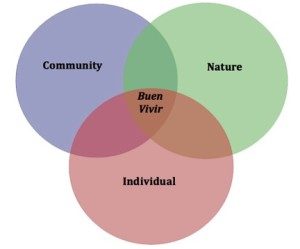

Further exploring the literature around this concept, Professor Mauricio Phélan of the Central University of Venezuela, who has studied this concept for years, granted me an interview and explained three distinct harmonies which exist within communities practicing buen vivir:

Harmony within yourself: physical, mental, and spiritual components

Harmony within yourself: physical, mental, and spiritual components- Harmony between communities: between yourself and your family, your community, your neighbors, your colleagues, institutions, and markets

- Harmony with nature: mutual balance between human activities and environmental health

When harmony within and amongst individuals, communities, and the natural world are achieved, then buen vivir is achieved.

Another academic perspective from Pablo Dávalos, an Ecuadorian economist, states that this alternative way of relating nature and society in a respectful manner can be achieved through a pluri-national state and intercultural society, as proposed by many indigenous communities.

Sumak Kawsay proposes a different relationship between human beings in which egotistical individuals should submit themselves to social responsibilities & ethical commitments and a relationship with nature in which nature is recognized as a fundamental part of human society. [It permits] a new vision of nature, without disavowing technological and productive advancements, but proposes a new contract with nature in which society is not separate from nature, doesn’t consider it external, a threat, a radical Other, but part of society’s dynamics and a fundamental part of future existence.

In order to accomplish this, Dávalos claims that we need to abandon our traditional concept of development “because it implies violence, imposition, and subordination. You can’t develop others because each society has their own worldview that you have to respect and, if in this worldview development nor linear time exist, then you can’t develop them thinking that you’re doing a social good when in reality you’re radically violating that society.”

How Buen Vivir is Unique

Through my research I came across countless variations and translations of buen vivir. Some of the more widely used terms in Latin America are:

- Buen Vivir (Spanish)

- Sumak Kawsay (Quechua)

- Suma Qamaña (Aymara)

- Lekil Kuxlejal (Mayan Tzeltal)

- Ñande Kaui (Ahcuar)

- Balu Wala (Kuna)

As this breadth of different languages reveals, the plethora of different cultures that hold worldviews similar to the concept of buen vivir each have, necessarily, their own unique definition.

Related Stories